|

|

|||||||

| ||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| ||||||||

|

|

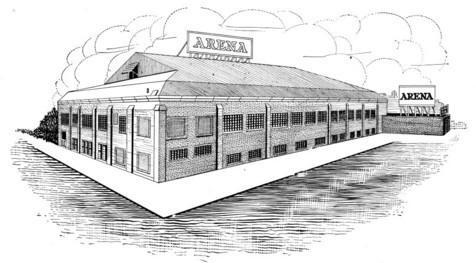

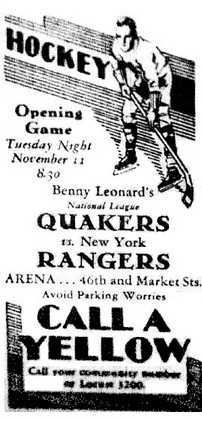

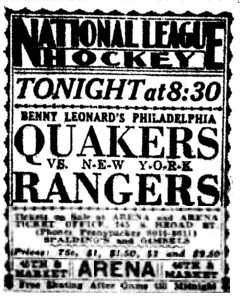

Introduction by Paul Christman Philadelphia’s first National Hockey League franchise, the Quakers of 1930-31, got its start in Pittsburgh in 1925. Then, the growing NHL welcomed two new franchises – the New York Americans and Pittsburgh Pirates. The league had come to the United States for the first time only the year before, with the birth of the Boston Bruins. Home ice for the Pirates was the ancient Duquesne Garden. It was first erected as a trolley barn in 1890 and converted into an arena seating about 5,000 six years later. Pittsburgh made the playoffs in 1926 and 1928 thanks to several star players. Two were future Hockey Hall of Fame members: defenseman Lionel Conacher, nicknamed “The Big Train” and voted Canada’s top athlete of the first half of the 20th century, as well as goalie Roy “Shrimp” Worters. But the city’s hockey fans never warmed up to the Pirates. Pittsburgh had a long, rich hockey heritage, but the middle-of-the-pack Pirates had to compete with memories of the popular Pittsburgh Yellow Jackets of the U.S. Amateur Hockey Association. The owner of the Jackets was the much-respected Roy Schooley, whose hockey background extended back to 1901. Schooley’s Jackets took the USAHA championship in 1924 and 1925. Unfortunately, the Schooley expertise would not transfer over to the Pirates. Financial problems forced Schooley to sell the Jackets to Pittsburgh attorney James Callahan and Duquesne Garden president Henry Townsend as the USAHA folded and the Jackets became the NHL Pirates. Attendance was a problem for the new Pirates right from the start. The team almost never sold out at the tiny Duquesne Garden in its five years in Pittsburgh. In later seasons, some of Pirate home games were played at their opponent’s rink or a neutral site to rake in a bigger gate. Pittsburgh drew an NHL-low 40,000 fans to their home games in 1927-28 (the Ottawa Senators were second worst, drawing almost 100,000). Rumors that the Pirates would move to another city hounded the team as early as 1926. Philadelphia and Cleveland headed the list of future homes, though in time Newark, New Haven, Atlantic City, and even Boston and Toronto were up for consideration. Talk of a transfer intensified when Henry Townsend died in January 1927. But the Townsend family and Callahan stayed with the Pirates, and the Pirates remained in Pittsburgh despite a rumors that surfaced in the press early in 1928 that the team would relocate to Philadelphia the following season. The gate had not been helped during the Pirates’ second season when the team made a very short-sighted trade. On December 16, 1926, Pirates captain Conacher was dealt to the New York Americans for $2,000 plus right wing Charlie Langlois, whose NHL career did not last past 1928. In contrast, Conacher starred in the NHL through 1937 and made the first or second NHL all star teams three times. Minus Conacher, Pittsburgh played at a 12-22-2 level the rest of 1926-27 and failed to make the playoffs. Conacher was said to be unhappy in Pittsburgh because he was not chosen to manage the team. Instead, the job went to Odie Cleghorn, who tried for a year to trade Conacher to the Boston Bruins for his brother Sprague. Boston refused to budge, and the trade for Langlois was eventually made. After the Pirates started 1927-28 poorly, Pittsburgh loaned Langlois to the Montreal Canadiens. Langlois spent the rest of the season in Montreal to end his NHL career. The Pirates made other player moves in December, most notably the acquisition of right wing Bert McCaffrey. That was enough to spark Pittsburgh. Their miserable 0-8-3 start was followed by a 19-9-5 spurt and a playoff berth. In October 1928, ex-boxer Benny Leonard reportedly headed a group that purchased the Pirates. Callahan was named team president. However, the franchise’s true owner remained behind the scenes. We now know what press reports from the early 1930s hinted at only once or twice: New York Americans owner William V. “Big Bill” Dwyer, a bootlegger, also owned the Pirates. Philadelphia Quaker forward Syd Howe said in a 1975 interview with Washington Post writer Robert Fachet that Leonard was the team’s general manager – and that Dwyer’s hand in the team was no secret to the players (“the team was owned by Dwyer … at least that’s what we were led to understand”). Benny Leonard had retired from boxing in 1925 as perhaps the greatest lightweight boxing champion of all time. He knew boxing but his knowledge of hockey proved to be no threat to Conn Smythe or Lester Patrick. And although he entered Pittsburgh saying he’d spare no expense to make the Pirates a first-rate team, he actually followed a much more tight-fisted policy. In 1949, Jim Coleman of the Toronto Globe and Mail interviewed Archie Campbell, the Quakers’ trainer. Campbell related a story of a late-night chat with the former boxer. Campbell quoted Leonard as saying, “With a Jew spending the money and a Scotchman [Callahan] watching where it’s going, they’ll never cheat us, Archie.” Leonard’s start with the franchise could hardly have been stormier. He and goaltender Worters got into a bitter salary dispute. After much acrimony and league intervention, Pittsburgh’s star netminder wound up with Dwyer’s Americans. In return, Leonard received $20,000 and Joe Miller, a competent goalie but not on a par with Worters. The trade of Worters to New York reunited him with Lionel Conacher. From a Pittsburgh perspective, both men had lent their considerable talents to the Pirates for far too short a time. Under Leonard, the Pirates headed steadily downhill. Pittsburgh’s hockey fans jammed Duquesne Garden for the first game under the Leonard regime but afterwards tended more and more to stay away. The Pirates won just nine games in 1928-29 and finished 21 points out of a playoff spot. Things only got worse in 1929-30, when the Pirates turned in a horrible 5-36-4 record. The final days in Pittsburgh were nightmarish. Seven out of the last 12 Pirate home games were played outside of Pittsburgh because fan support in that city had dwindled to nothing. On February 22, 1930, only 300 unenthusiastic fans attended a home game played in Pittsburgh versus the Montreal Maroons. The Duquesne Garden’s ghastly state only contributed to the team’s misfortunes. Not only did the Garden have far too few seats to be profitable and lack any comforts or conveniences by 1930 standards, the antiquated ice-making system required four days to produce a playable ice surface (versus four hours for a modern rink, a 1931 Pittsburgh Press story reported). Though a new arena was desperately needed, Pittsburgh’s proposed Town Hall entertainment center was going nowhere (and there was no assurance that a rink would even be part of it). Columnists accused Leonard of penny-pinching himself into the predicament. Ralph Davis of the Pittsburgh Press wrote, “Leonard will have to cut the purse strings and pay well for new talent on a par with that owned by rival clubs, if he expects to make any money here next winter.” He pointedly added, “Fans here cannot be fooled about the brand of hockey served up to them.” Finally, the stock market collapse of October 1929 only made the Pirates’ outlook that much worse. The steel industry was in a sharp decline, and Pittsburgh’s citizenry cut back as jobs and income were lost. Al Clark of the Press concluded, “Pittsburgh’s hopes for a National Hockey League berth next season have grown as cold as a mother-in-law’s kiss.” The Pirates could not play to a virtually empty Duquesne Garden in 1930-31, but where could the team go? In the spring of 1930, word spread that the Pirates would be transferred to Atlantic City until a suitable arena in Cleveland could be built. The deal appeared promising, but it quickly melted away in July. Philadelphia represented the other principal alternative, but hockey was relatively new to the city and there was no push to replace the 6,000-seat, 10-year-old Philadelphia Arena at Market and 45th Streets. The Arena was adequate for the Philadelphia Arrows of the Canadian-American Hockey League, but well below NHL standards. In the end, however, Philadelphia was the only feasible alternative left. But the Pirate hierarchy thought of it only as a temporary solution. When the Pirates headed east to Philadelphia in mid-October, the door was left wide open for the franchise’s return to Pittsburgh. The team was in Callahan’s hands until Leonard’s final payment for the Pirates came through (it was due April 1, 1931). Callahan kept the official name of “The Pittsburgh Professional Hockey Club” for the team, though it would now be known as the Philadelphia Quakers. The Pirates retained exclusive control of the hockey territory in Pittsburgh. In an October 23, 1930 story in the Pittsburgh Press, Callahan left little doubt about his intentions. He said, “We are looking to the future and realize if Pittsburgh is to occupy the high place it once did in hockey we must start at the bottom and develop players.” He added, “Pittsburgh will be back in the National Hockey League as soon as we have a suitable place to play in,” by which time “we will have a team developed.” The Press took these plans a few steps further. If a new International Hockey League team were to come to Pittsburgh, it would be used as a farm team for the Pirates when the Pirates made their return. It was expected that the Town Hall would be built in two years – the amount of time needed to build a team. The IHL came to Pittsburgh in 1930-31, taking to the ice as a new Yellow Jackets team. Town Hall would never be built. All of this likely would have been news to readers of the Philadelphia Inquirer or Bulletin. At the time of the franchise shift, the papers told Philadelphians that the franchise would return to Pittsburgh if that city provided it with a new arena. In that case, Philadelphia and Cleveland would then get expansion franchises in a 12-team NHL to come in the next year or two. But it would soon be clear that the Great Depression was deepening and that the NHL had to consider trimming its deadwood, not branching out. As the 1930-31 season approached, the Philadelphia press focused on the newcomers’ prospects in new surroundings with a new coach, retired NHL referee in chief Cooper Smeaton. Leonard, of course, did nothing to discourage Philadelphians from thinking the franchise would stay put in its new home. “This season marks the inauguration of National League Hockey in Philadelphia,” he declared in a message in the Quaker home programs. “It is our desire to take every step that will add to your enjoyment and comfort and further your interest in Ice Hockey. Always remember that this team is YOUR TEAM.” Leonard took every opportunity to talk up the prospects of the Quakers. After he acquired young talents of Syd Howe, Wally Kilrea, and Allen Shields from Ottawa – economically, on a loan basis – Leonard said, “This is only the first move to bring a winner here. We must make a good start and I will spare no expense to give the fans what they want. We have other deals in mind which will be consumed if the men we have now fail to deliver.” But did Leonard have the money in the bank to back his promises? Gerald Eskenazi wrote in his 1973 book, “Hockey,” that coach Smeaton was forced to fund four road trips out of his own pocket. Eskanazi also said that Smeaton and his Quakers were nearly stranded at a train station when a check meant to cover the team’s trip to Chicago bounced. Leonard could not be reached, but a phone call to Leonard’s lawyer produced the needed money just as the Chicago-bound train was about to pull out. Syd Howe told the Washington Post in 1975, “Those were depression years and we were making pretty good money, $3,500 to $4,000. We were getting paid pretty regular, too, although sometimes it was an off-and-on thing.” Leonard’s Quakers prepared to open their season with a home game in the Philadelphia Arena, which was a good 25 years century younger than the aged Duquesne Garden. But Arena, completed in 1920, was a small rink with poor sightlines that had already been outclassed by the larger rinks erected in the mid-1920s that most other NHL teams called home. Leonard told the Philadelphia press that his players would improve now that they had an iron-fisted new coach in Smeaton, who was making his first and only try at managing an NHL team. Hockey writers outside of the Philadelphia area predicted that the Quakers would be no better than the Pirates that preceded them. The Quaker skaters, Leonard Cohen of the New York Post wrote after the season opened, “are nothing to throw your hat in the air over. … The Philly hosts look like the weakest force in the circuit on paper; they’re every bit of that on the ice.” But the Philadelphia sportswriters were having little of that. Newcomers Howe, Kilrea, and Shields, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported said two days before the season’s opening night, “hopped into the Sunday morning practice at the Arena and proved to be in great shape. They have been on the ice since the middle of October and are down fine.” The Inquirer played the upcoming opening game with the New York Rangers as another chapter in the sports rivalry between New York and Philadelphia, then best represented by baseball’s famed New York Yankees and Philadelphia Athletics, each of whom wore the World Series crown for two out of the four years from 1927 through 1930. Leonard stood behind the players he had in training camp. He said, “Once you see them in action, you will say they have the goods.” Benny said he intended to train the players himself. And he proclaimed, “I feel certain Philadelphia hockey fans will like the men who will represent this city in the National League. I want to produce a winning club. If I don’t, it won’t be my fault.” Coach Smeaton, Leonard said, knew the game “from A to Z.” That had to be why Smeaton was more cautious. Before the season started, he told the Philadelphia writers, “I know there are better teams than the Quakers in the league, but we are going to have a fighting combination.” The Quakers were not ones to avoid a fight. Shields and fellow defenseman D’Arcy Coulson were among the league-leaders in penalty minutes. But the Quakers would soon show that the 1929-30 Pirates with their 5-35-3 record had not quite reached rock bottom. For the Quakers’ first match, played in Philadelphia on November 11, 1930, Leonard went all out. The ushers were dressed in tuxedos. Colorful flags were hung from the Arena’s ceiling. The Quakers emerged in new uniforms that preserved the orange and black colors of the 1929-30 Pirates. But the debut was hardly a success. The visiting New York Rangers won 3-0. Stanley Woodward of the New York Herald Tribune wrote, “When it became apparent that the transplanted Pirates were not going to do any business the crowd, which could not have numbered more than 4,000, began to make caustic remarks and during the third period a large number of fans left the rink.” Only 2,000 appeared for the second Quakers home game a week later. The Quakers got off to a disappointing 0-4-1 start. They were unable to even score a goal until their third game. But, to everyone’s surprise, the Quakers chalked up their first win in their sixth contest when they beat Toronto, 2-1, in a home game played November 25. The win ended the Maple Leaf streak of five straight shutouts to open the season. It was enough to briefly raise the hopes of Philadelphia fans and writers. “Mr. Benny Leonard’s Philadelphia Quaker ice hockeyists went major league last night,” wrote Bill Dooley of the Philadelphia Record. Earl Eby of the Philadelphia Bulletin noted that the entire NHL “was rendered groggy by the thud,” and fans leaving the Arena were “dizzy from the excitement.” Stan Baumgartner of the Philadelphia Inquirer wrote, “The great improvement shown by Smeaton’s club swept the fans by storm. In three short weeks they have changed from a loosely knit organization to a finely balanced unit.” Cooper Smeaton took this win as a sign of better things to come. He told the Record, “We are off now. Now that we have our first victory I believe we will soon have many more points in our column. It took us some time to get started but I think we are now in proper condition and we can defeat many of the teams in either the Canadian or American divisions.” However, Bert Perry of the Toronto Globe revealed several months later that the Leafs were guilty of overconfidence. They had taken it easy for two periods, and the Quakers managed to hold off the Leaf comeback try in the third. If so, the rest of the NHL went out if its way not to make the same mistake. The Philadelphians followed up their upset of Toronto with a streak of 15 consecutive Quaker defeats, at that time an NHL record. Only three NHL teams have topped the mark since then. Though five of the 15 losses were by only one goal and another two losses were only by two, the Quakers suffered some notable blowouts during the streak. The most memorable was unquestionably the 8-0 loss at the Boston Garden on Christmas night. As the New York Post said, the Garden was the scene of “the dullest game of hockey and one of the best free-for-alls seen in years.” Actually, two fights broke out in the third period. The first required the help of a dozen policemen to restore calm. LeRoy Atkinson of the Boston Evening Transcript wrote that the officers were “slipping, falling, and sliding.” Six fighting majors were handed out for the first fight, with accompanying $15 fines. The Quakers finally broke their 15-game losing skid with an overtime win against the visiting Montreal Maroons January 10. Quaker forward “Peaches” Lyons broke a 3-3 tie midway through a 10-minute overtime. Under the rules of the time, the Quakers had to hold onto their slim lead for the rest of the overtime period to register a win. When they did, Hooley Smith and Babe Siebert of the Maroons broke their sticks over the Arena’s boards in disgust. Leonard and Smeaton blended in some younger players as the season wore on. It did no good. Smeaton’s squad scraped together only a win and a tie each month, except for the completely lost month of December. When the Quakers managed to sidestep a loss, it could be very noteworthy. They followed up their horrendous 8-0 loss at the Boston Garden with a fine 3-3 tie on their return to Boston a month later. In February, Quaker goalie Wilf Cude registered a shutout on the road when the Quakers won at Detroit 2-0. The next month, the Quakers went on a one-game scoring spree when they defeated Detroit again, this time at home by a 7-5 score. In their final game of the season, Philadelphia traveled to the Montreal Forum and almost came away with a win versus the eventual Stanley Cup champion Montreal Canadiens. Montreal scored a disputed tying goal with only 15 seconds left. Cude earned applause from the Montreal crowd when he played to the end of the game despite being knocked unconscious for several minutes in the second period by a shot off the stick of famed Canadien forward Howie Morenz. Not surprisingly, Philadelphia’s hockey fans preferred the CAHL Arrows to the Quakers. The Arrows, who would struggle unsuccessfully for a playoff spot themselves, nevertheless drew 4,000 fans on an average night, versus 2,500 for the Quakers. Prior to the Quakers’ win over the Maroons, Leonard denied press reports that he might transfer the Quakers to another city. “We are here to stay,” he said. “I have confidence in Philadelphia as a major league hockey town.” He added, “You know, I wouldn’t say that Philadelphia has had a chance to see major league hockey.” The team wasn’t exactly missed back in Pittsburgh. “Benny Leonard’s Pirates in the Quaker City are starving,” Ralph Davis of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette bluntly noted in mid-January. Though Leonard gradually disappeared from the Philadelphia hockey columns as the season progressed, he was spotted at the last Quakers home game on March 17, 1931. Earl Eby of the Philadelphia Bulletin wrote that he found Leonard in a “rather cheerful mood,” and that Leonard – always the promoter – told him, “We’ll have a winner next year. Wait and see!” But the following year, when the Quakers did not return to the ice, Leonard made an ill-advised comeback as a boxer to recover some of his financial losses in the stock market and hockey. The Quakers ended 1930-31 with a final 4-36-4 record. That represented a .136 winning percentage, the second-worst pace in NHL history. Only the 1974-75 Washington Capitals, who won at a .131 clip, have fared worse. On September 26, 1931, the NHL suspended the Ottawa Senators and Philadelphia Quakers franchises for one year. Canadian papers mourned the loss of the once-proud Senators franchise but said the Quakers would not be missed. On the U.S. side, even the Philadelphia press briefly acknowledged the Quakers’ banishment and virtually forgot the team from that moment on. Ottawa would return to the NHL in 1932-33 before relocating to St. Louis for a year and then disbanding in 1935. There was talk of reviving the Pirates, with the team’s year in Philadelphia was pretty much forgotten. However, despite tantalizing reports in the papers that hinted that a new arena in Pittsburgh was right around the corner, the league suspended the franchise again and again until it was formally killed off at last in May 1936. By that time, all hopes for Pittsburgh’s proposed Town Hall had disappeared, thanks in large part to many legal fights over its planned location. “It was a scrappy team, but there wasn’t enough talent,” Syd Howe said of the Quakers in his 1975 interview with the Washington Post. “The crowds were small. People in Philadelphia were not educated to hockey at that time.” Howe was undoubtedly the Quaker who tasted the most success. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1965. The Quakers had several other decent players. Those who had the longest NHL careers were, in 1930-31, either talented youngsters like Howe who lacked experience or talented veterans who had been with the Pirates and whose best days were behind them. For the most part, the rest of the Quakers roster was composed of journeymen. In the end, no one missed the team after its demise. The other NHL teams had tired of the smaller attendances the Quakers practically guaranteed in their rinks. Philadelphia was not left without hockey. The city was represented (often not well) by the Arrows and several other minor league teams that came in their wake until the Flyers entered the NHL in 1967. Paul Christman is collecting information on the first NHL team to call Philadelphia (and Pittsburgh) home. Any contributions that you have to Quakers or Pirates lore – accounts passed down, photos, or any sort of lead – would be appreciated and acknowledged. Even if you just want more information on the Quakers or Pirates, please contact Paul at paul.christman@wolterskluwer.com. |

|

|

|

|

|

Inquirer ads for the first Quakers games (courtesy Paul Christman) |

|

| Date | Road | Home | ||||

| 11-Nov-30 | Rangers | 3 | @ | Quakers | 0 | Boxscore |

| 15-Nov-30 | Quakers | 0 | @ | Toronto | 4 | Boxscore |

| 16-Nov-30 | Quakers | 1 | @ | Detroit | 5 | Boxscore |

| 18-Nov-30 | Ottawa | 2 | @ | Quakers | 2 (ot) | Boxscore |

| 23-Nov-30 | Quakers | 2 | @ | Rangers | 5 | Boxscore |

| 25-Nov-30 | Toronto | 1 | @ | Quakers | 2 | Boxscore |

| 29-Nov-30 | Rangers | 6 | @ | Quakers | 3 | Boxscore |

| 2-Dec-30 | Canadiens | 2 | @ | Quakers | 0 | Boxscore |

| 4-Dec-30 | Quakers | 2 | @ | Ottawa | 5 | Boxscore |

| 6-Dec-30 | Boston | 4 | @ | Quakers | 3 | Boxscore |

| 9-Dec-30 | Americans | 2 | @ | Quakers | 1 (ot) | Boxscore |

| 13-Dec-30 | Detroit | 3 | @ | Quakers | 2 | Boxscore |

| 16-Dec-30 | Quakers | 0 | @ | Americans | 3 | Boxscore |

| 20-Dec-30 | Quakers | 1 | @ | Montreal | 5 | Boxscore |

| 23-Dec-30 | Chicago | 3 | @ | Quakers | 2 | Boxscore |

| 25-Dec-30 | Quakers | 0 | @ | Boston | 8 | Boxscore |

| 28-Dec-30 | Quakers | 2 | @ | Rangers | 4 | Boxscore |

| 1-Jan-31 | Quakers | 3 | @ | Chicago | 10 | Boxscore |

| 3-Jan-31 | Ottawa | 5 | @ | Quakers | 4 (ot) | Boxscore |

| 4-Jan-31 | Quakers | 0 | @ | Americans | 5 | Boxscore |

| 8-Jan-31 | Chicago | 4 | @ | Quakers | 0 | Boxscore |

| 10-Jan-31 | Montreal | 3 | @ | Quakers | 4 (ot) | Boxscore |

| 13-Jan-31 | Canadiens | 2 | @ | Quakers | 1 | Boxscore |

| 17-Jan-31 | Detroit | 5 | @ | Quakers | 2 | Boxscore |

| 20-Jan-31 | Quakers | 2 | @ | Detroit | 5 | Boxscore |

| 22-Jan-31 | Quakers | 2 | @ | Chicago | 5 | Boxscore |

| 24-Jan-31 | Boston | 4 | @ | Quakers | 2 | Boxscore |

| 27-Jan-31 | Quakers | 3 | @ | Boston | 3 (ot) | Boxscore |

| 29-Jan-31 | Quakers | 1 | @ | Canadiens | 7 | Boxscore |

| 31-Jan-31 | Quakers | 2 | @ | Toronto | 3 | Boxscore |

| 5-Feb-31 | Quakers | 1 | @ | Chicago | 6 | Boxscore |

| 10-Feb-31 | Rangers | 3 | @ | Quakers | 1 | Boxscore |

| 14-Feb-31 | Americans | 1 | @ | Quakers | 1 (ot) | Boxscore |

| 17-Feb-31 | Quakers | 2 | @ | Detroit | 0 | Boxscore |

| 22-Feb-31 | Quakers | 1 | @ | Rangers | 6 | Boxscore |

| 24-Feb-31 | Boston | 5 | @ | Quakers | 1 | Boxscore |

| 28-Feb-31 | Quakers | 1 | @ | Montreal | 4 | Boxscore |

| 3-Mar-31 | Toronto | 5 | @ | Quakers | 1 | Boxscore |

| 7-Mar-31 | Quakers | 2 | @ | Boston | 7 | Boxscore |

| 10-Mar-31 | Quakers | 3 | @ | Ottawa | 5 (ot) | Boxscore |

| 12-Mar-31 | Detroit | 5 | @ | Quakers | 7 | Boxscore |

| 14-Mar-31 | Montreal | 3 | @ | Quakers | 2 | Boxscore |

| 17-Mar-31 | Chicago | 4 | @ | Quakers | 0 | Boxscore |

| 21-Mar-31 | Quakers | 4 | @ | Canadiens | 4 (ot) | Boxscore |

Key Personnel |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

W-L-T Record |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Playoff Games |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| -none- | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Leaders |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Scoring Stats |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Click on G,A or PIM for complete list or GP for game-by-game stats |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Goaltending Stats |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Click on GP for game-by-game stats |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Shutouts |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opening Games |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Trades |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Other Transactions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Injuries |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

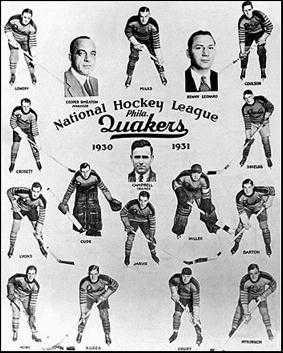

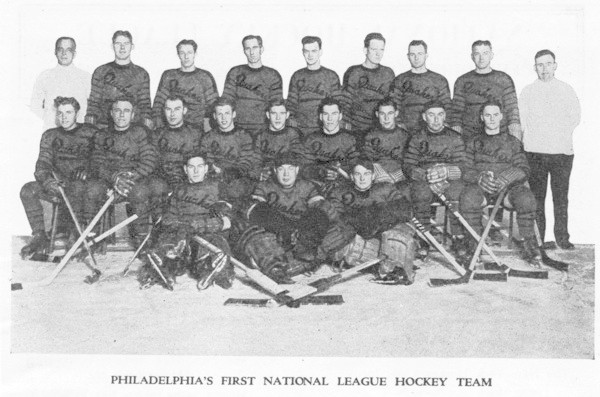

Back row: Cooper Smeaton (coach), Allen Shields, Rennison Manners, Rodger Smith, Tex White, Gord Fraser, Harold Darragh, Hib Milks, Archie Campbell (trainer)

Middle row: Aubrey Webster, John McKinnon, Tom Cowan, Syd Howe, Wally Kilrea, Bud Jarvis, Cliff Barton, Herb Drury, Gerry Lowrey

Front row: Andrew Spooner (?), Joe Miller, Wilf Cude